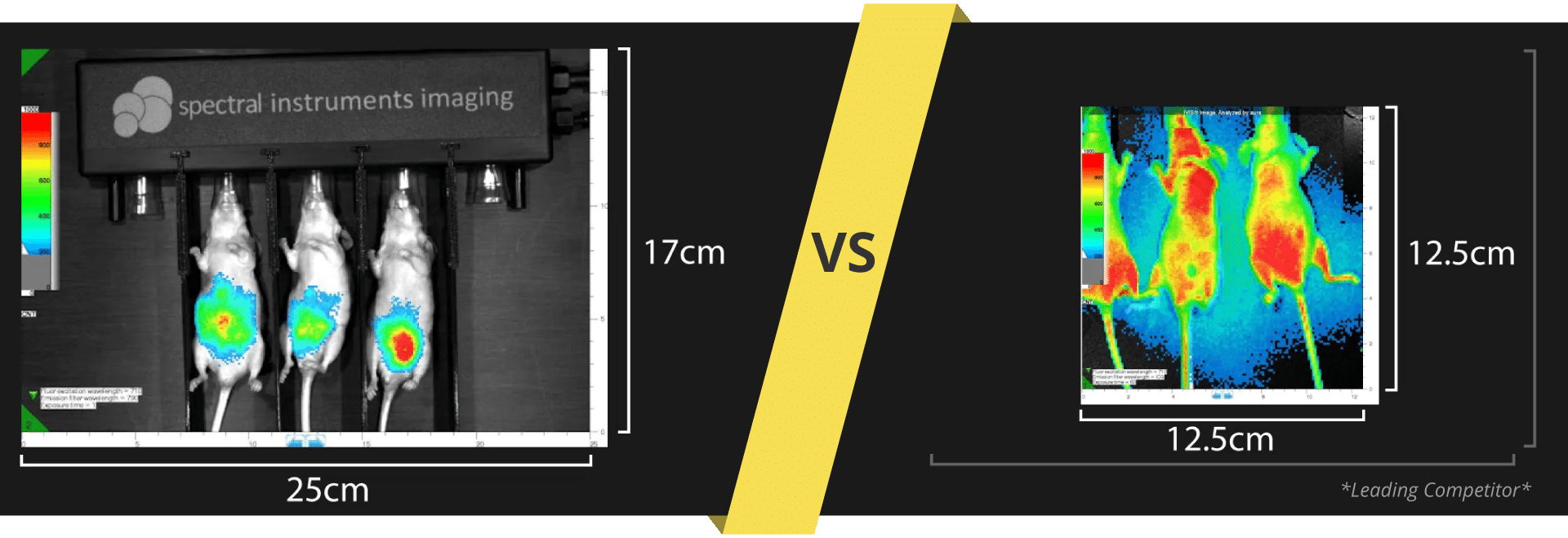

What's the difference between these data sets?

Specificity

Experiment Details

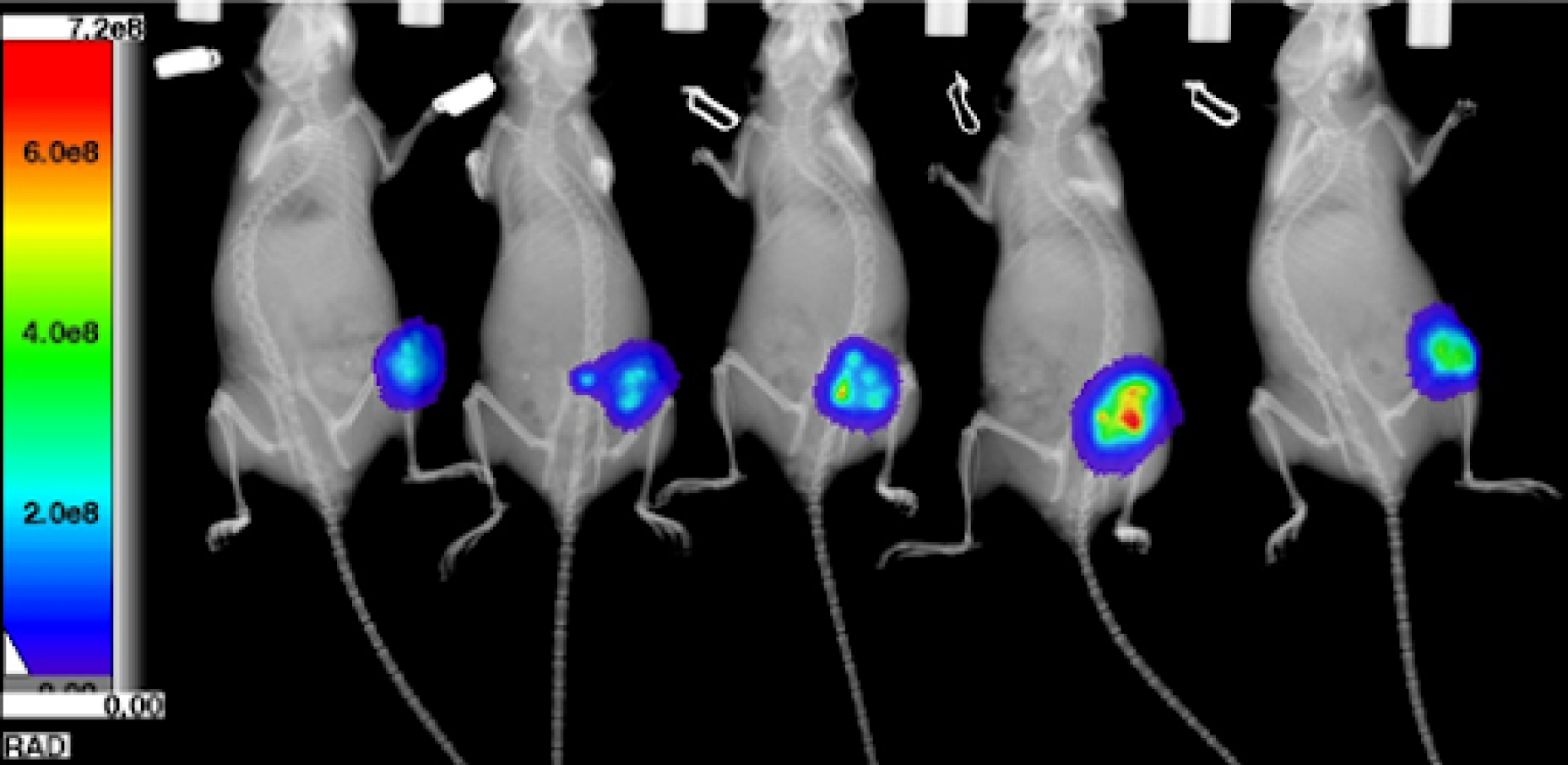

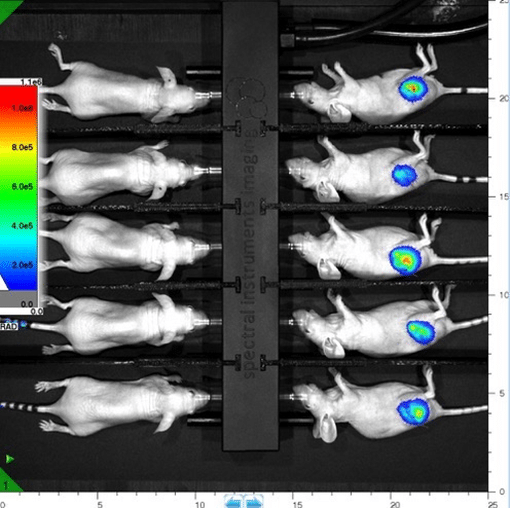

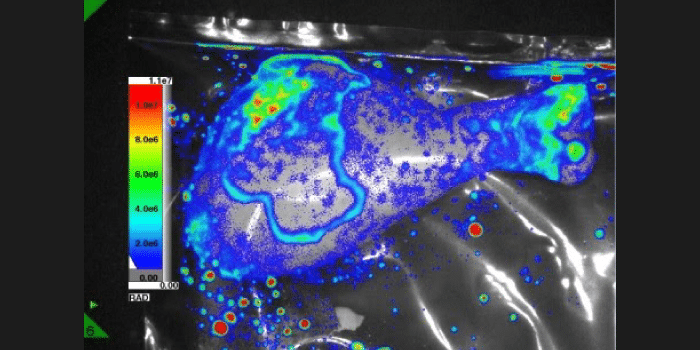

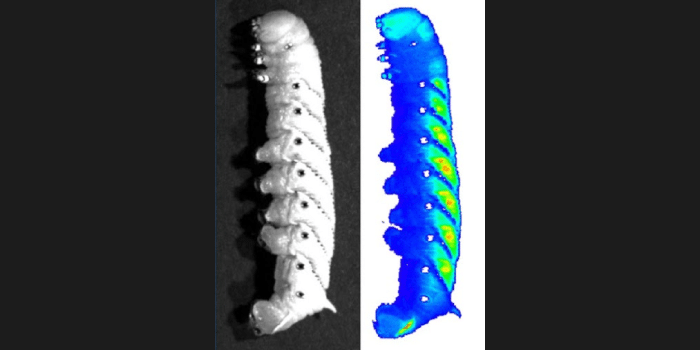

FLI Specificity Experiment:

Experimental NIRF probe: ICG-like

Probe max Ex/Em = 710/790 nm

Test Mice (n=3): Received ICG-like injection, IP

All mice imaged immediately after IP injection

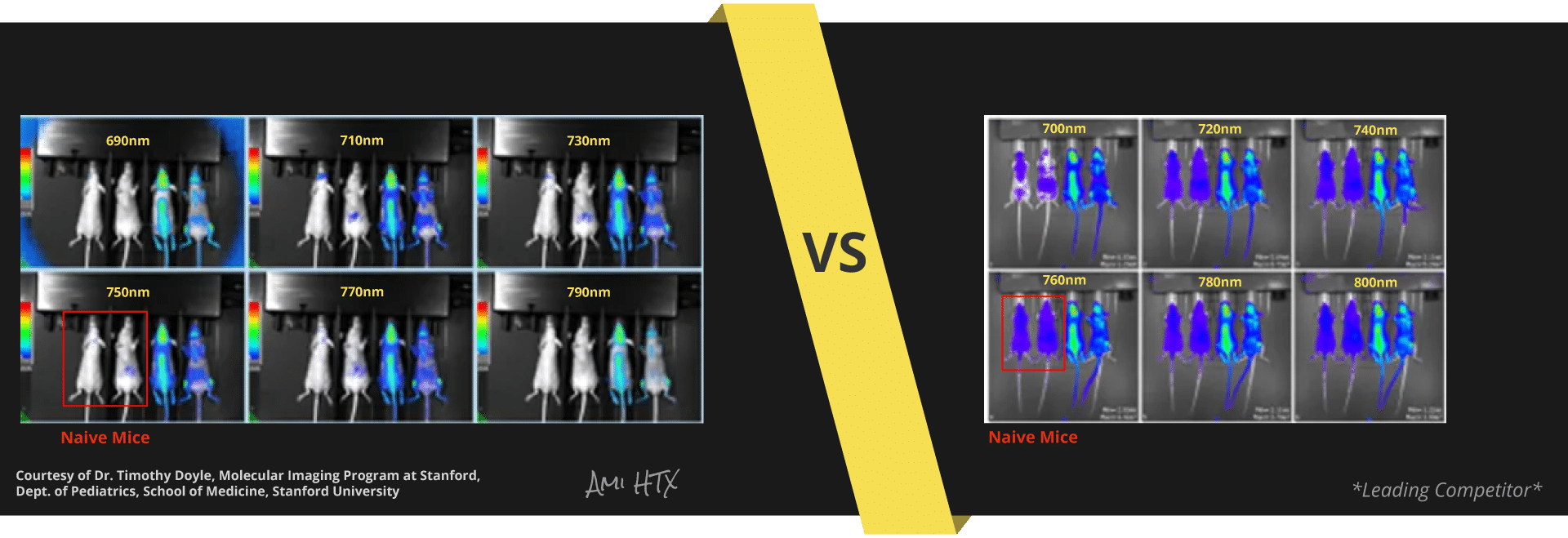

Experiment Details

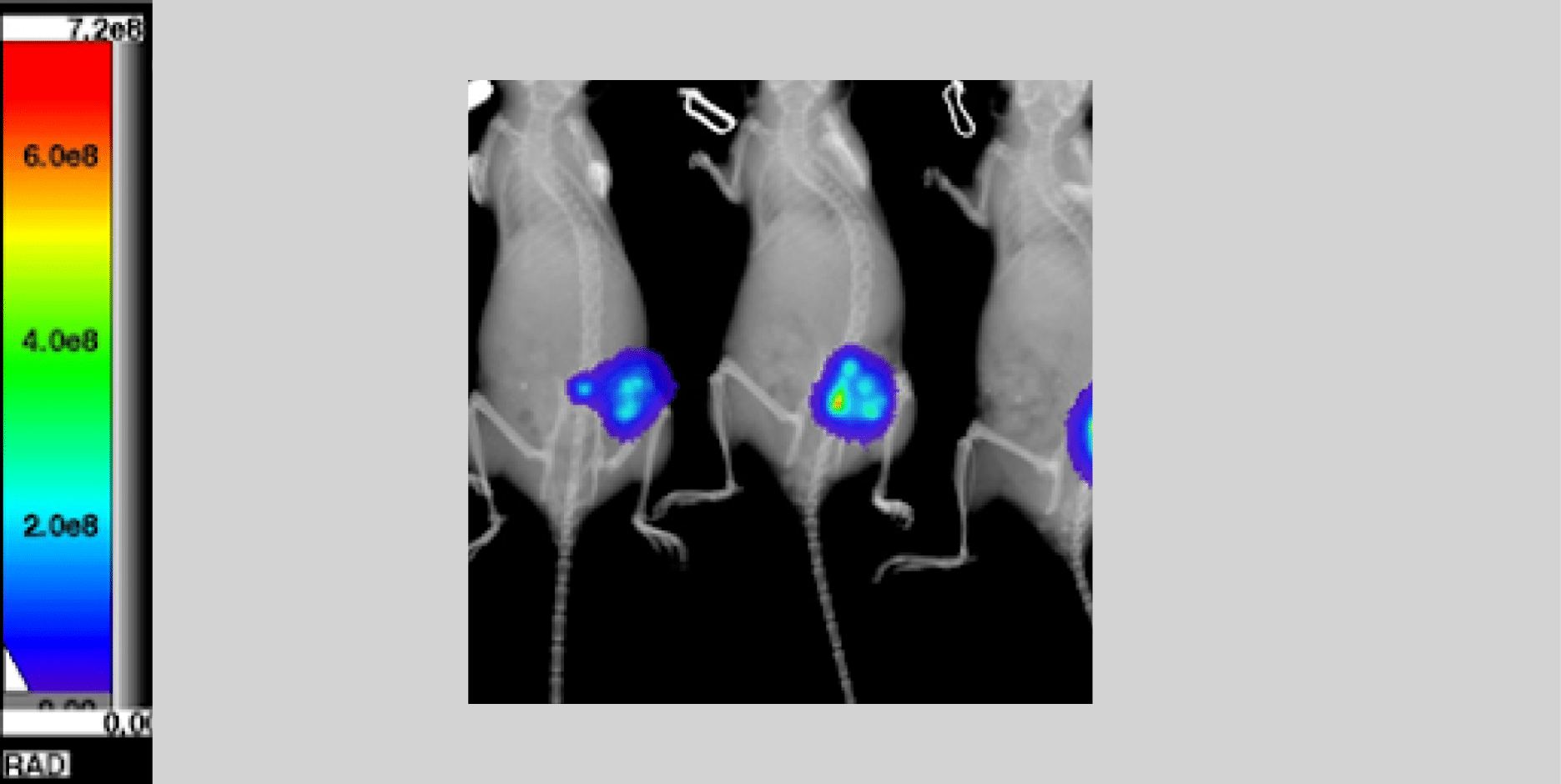

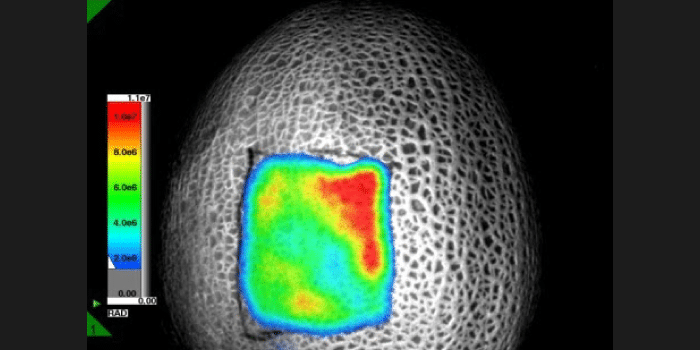

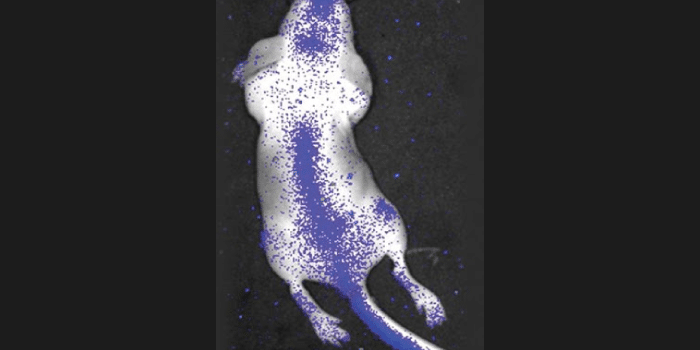

FLI Specificity Experiment:

NIRF probe: OsteosenseTM 680; targets hydroxyapatite in growth plates of long bones

Probe max Ex/Em = 668/687 nm

Test Mice (n=2): 100uL Osteosense™680, IP

Control mice (n=2): 100 uL PBS, IP

All mice imaged 24 hrs post IP injection

Orientation during imaging: Mice 1, 3: dorsal | Mice 2, 4: ventral

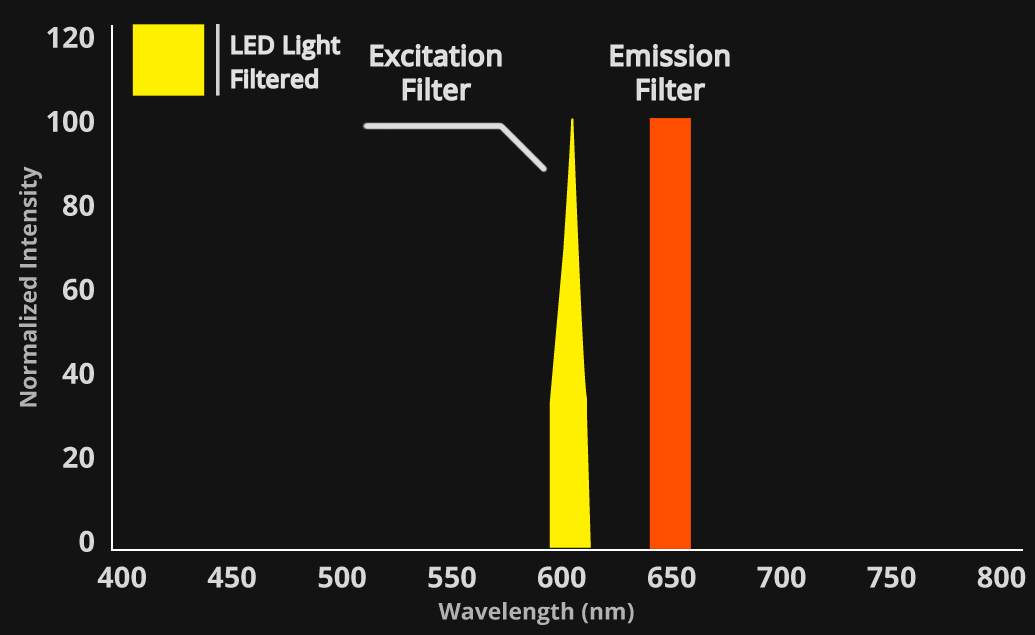

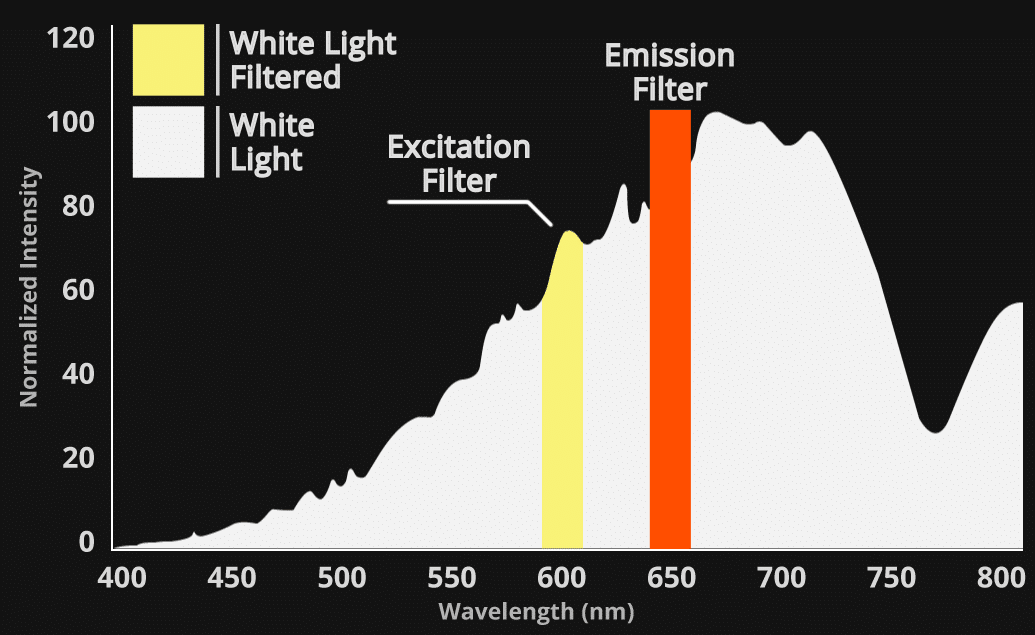

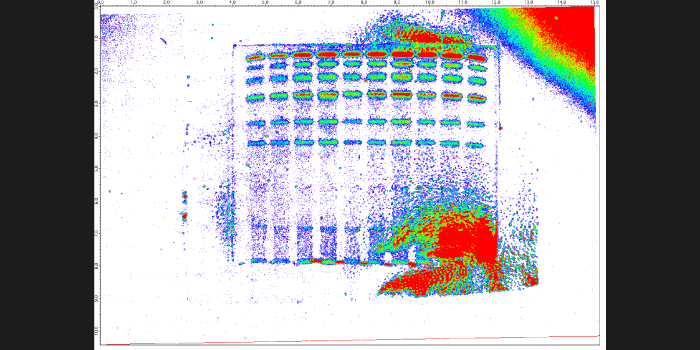

The physics behind the data:

LED spectrums are inherently narrow and specific – falling within the 20 nm filter bandwidth

White light has a broad emission and relies on filters to limit 93.5% of light. Out-of-band photons result from the physical limitations of filters blocking excessive light.

Conclusion:

Out-of-band, excitation-based light is detected across a range of Em filters in white light based competitors. This non-specific, out-of-band light, reflects off mice, reducing Signal/Noise ratio.

Ready to Start Multiplexing?

Use multiple probes to answer complex biological questions. Find out how our patented LED technology can help.

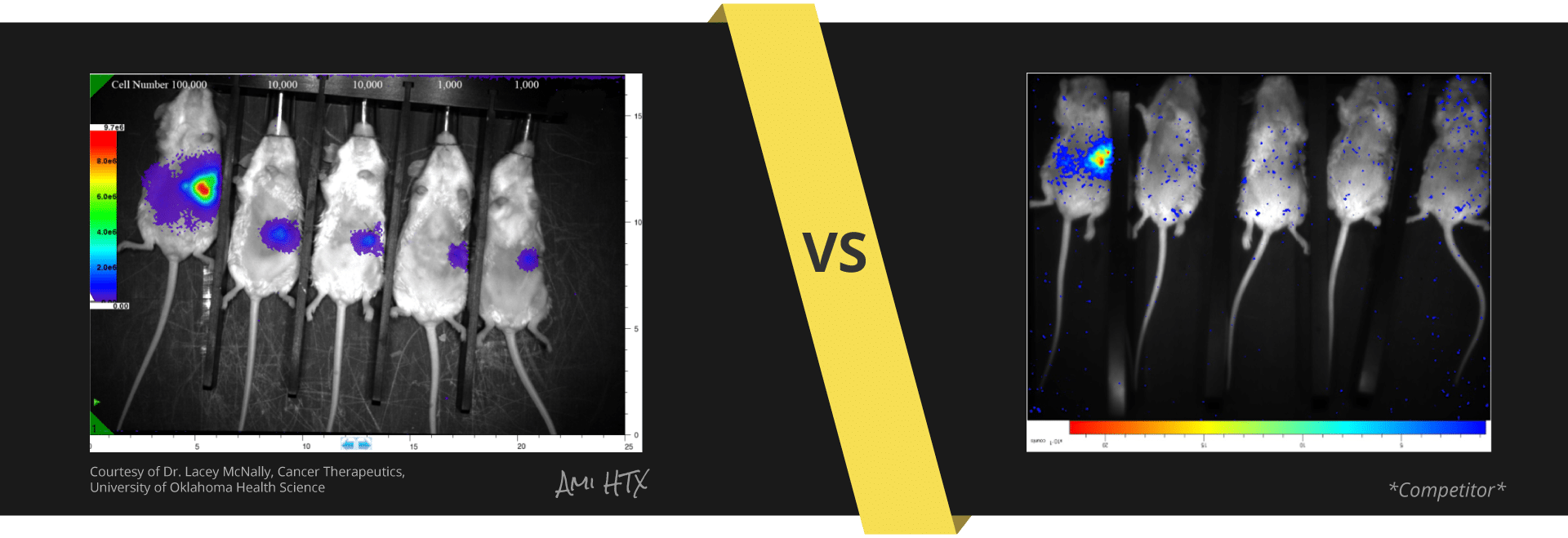

High Sensitivity + Low Background = Accurate Quantification

Individually controlled LED’s allow you to avoid overlapping fluorescent spectra entirely – providing clean, multiplex fluorescent data.

Continuous light from white tungsten bulb requires software algorithms to artificially separate spectra.

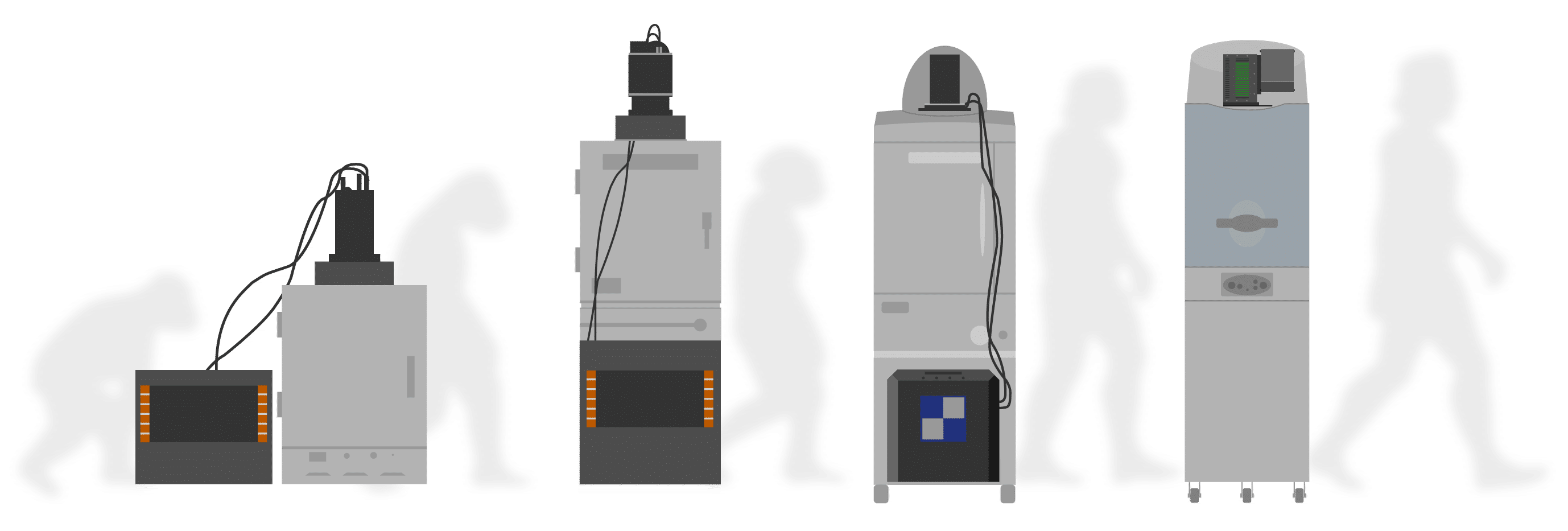

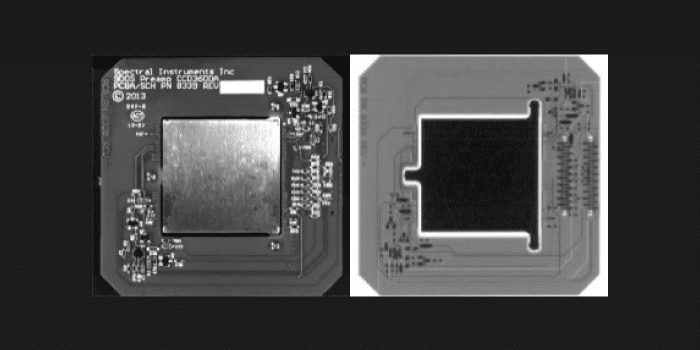

Evolution of -90°C Absolute Cooling

CryoTiger:

A multiple gas condensation system. Slow, noisy, and prone to failure

Water Chiller System:

Faster, but liquid plumbing still susceptible to leaks

Electronic, air-cooled system:

No leaks, fast cooling down to -90˚C absolute in 5 minutes

Solid State Cooling Guarantees No Leaks!

No liquids or gas chillers.

Reaches -90°C absolute in only 5 minutes.

Learn more about the importance of Ultra Cold CCD Cameras

Ultra Cold for Deeper Scientific Insights

-90°c Absolute

-20°c

-90°c Absolute

-20°c

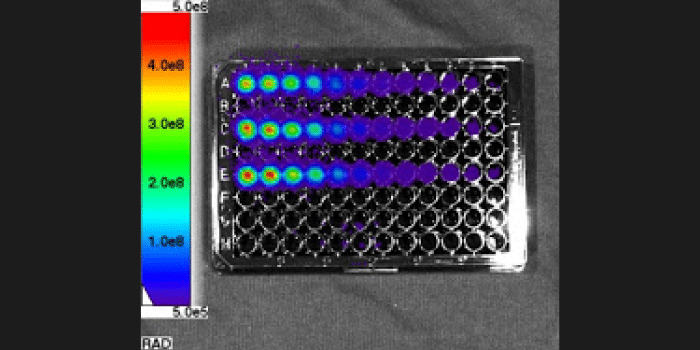

Experiment Details

BLI Sensitivity Experiment:

Luciferase probe: Human pancreatic cell line S2VP10

All mice received IP injection of 2.5 mg luciferin 10 min prior to imaging

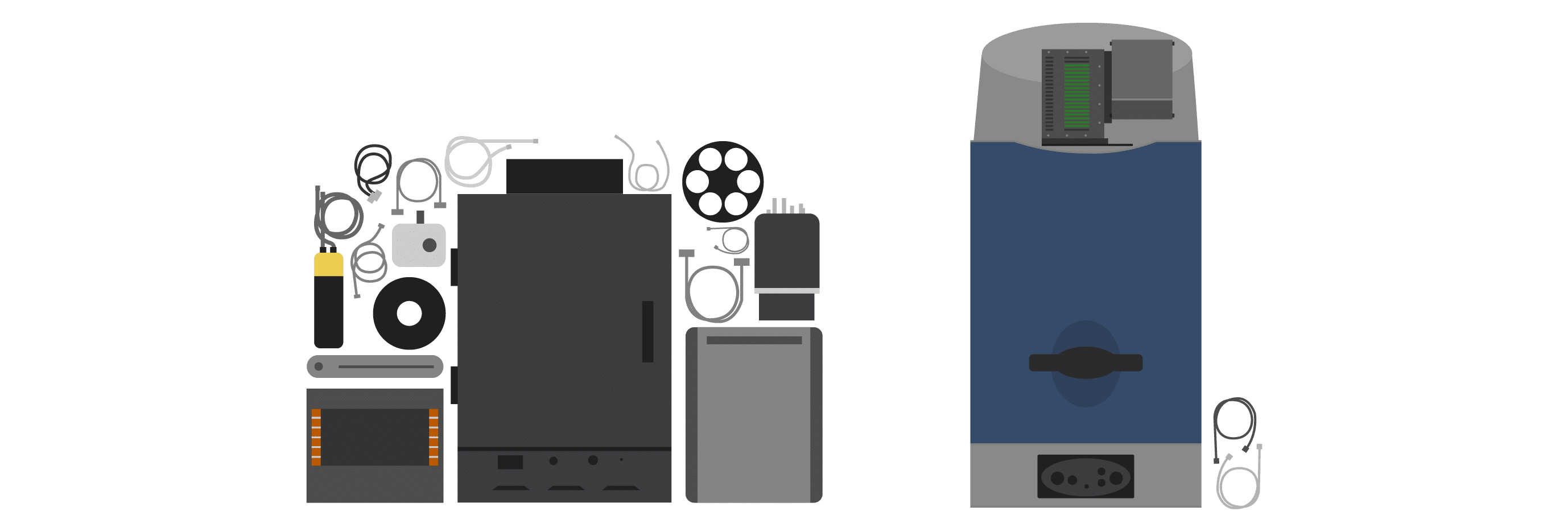

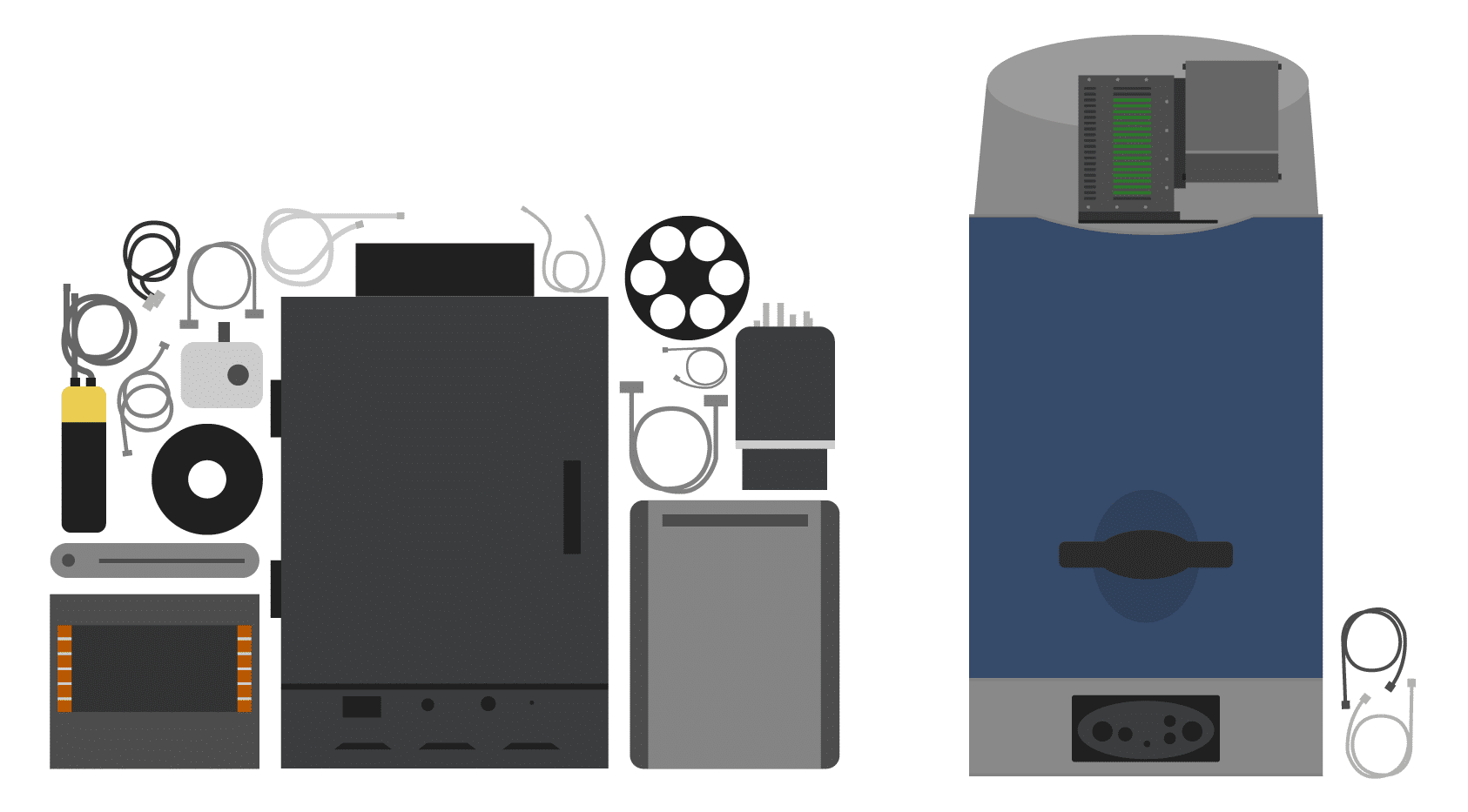

Tired of Expensive Repair Bills?

Spectral’s engineering team eliminated

failure-prone gaskets, limit switches, wires, connectors, computer cards and external controllers

ensuring a factory calibrated, robust, and modern design

Less Pieces and Parts to Break = Lower Lifetime Cost of Ownership

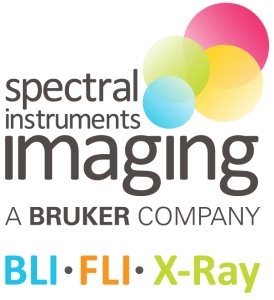

High Capacity In vivo Imaging

High Capacity In vivo Imaging Now Available on your Benchtop

Now Available on your Benchtop

Ami HTX FoV 25x17cm

Allows you to easily image 5 mice in a single exposure

Courtesy of Dr. Jun Wu | Stanford University School of Medicine

Ami HTX

Leading Competitor FOV 10x10cm

*Representing Leading Competitor FOV

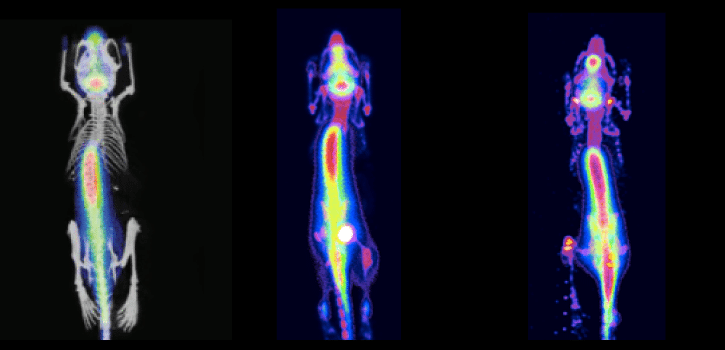

Lago X Raising the Bar

Sharon S. Hori, Sheen-Woo Lee, Sanjiv Sam Gambhir (Canary Center at Stanford, Stanford University School of Medicine)

- Designed for those who considerer small animal imaging to be their life’s work

- Industry leading 10 mouse capacity with 25 x 25 cm FOV

- Unrivaled Sensitivity (45 M.D.R.)

- 14 Excitation LEDs and 20 Emission Filters

- Multi Modality Coregistration

- Quantitative 3D Optical Imaging

Multi Modality Coregistration

Quantitative 3D Optical Imaging

Imagine the Possibilities

Experts trust Experts

Spectral Instruments Imaging is the fusion of principal developers in in vivo imaging technology and a world class camera manufacturer. Working together to advance pre-clinical imaging to reveal complex biological processes.

Frequently Asked Questions

BLI is best for tracking cell populations, monitoring tumor growth, or measuring gene expression due to its sensitivity and low background. FLI is well suited for biodistribution studies, nanoparticle tracking, and multiplexed imaging using different fluorophores.

Bioluminescence imaging relies on luciferase enzymes that emit light when exposed to a substrate (for example, D-luciferin). It produces very low background noise and is ideal for sensitive detection of cells or molecular activity. Fluorescence imaging uses fluorescent probes or proteins excited by an external light source, offering multiplexing capabilities and more flexibility in probe selection.

Bioluminescence is an enzymatic biological process involving a luciferase that catalyzes a luciferin substrate in the presence of oxygen to produce light. This process results in a high signal-to-noise ratio because the animal produces very little background light (some chemiluminescence and phosphorescence) and no external excitation light is needed.

Fluorescence requires an external light source to excite a fluorescent target molecule/reporter (e.g., proteins or dyes). In vivo fluorescent imaging has a lower signal-to-noise ratio compared to bioluminescent imaging. In addition, to better optimize fluorescent imaging it is necessary to excite and capture light at defined wavelengths corresponding to the peak excitation and emission wavelengths of the fluorochrome being used (e.g., using defined wavelength LED and bandpass filters).

BLI is generally more sensitive because it does not rely on external excitation light, resulting in extremely low background noise. This allows detection of very small numbers of viable (live) cells in vivo, even in deep tissues. Fluorescence imaging (FLI), by contrast, has a higher background due to excitation light, but it enables multiplexed detection and can be used with samples that are no longer alive, making it valuable for endpoint studies, tissue sections, and assays where cell viability is not a requirement.

If your goal is to monitor live cell dynamics or longitudinal processes such as tumor growth, infection, or gene expression, choose a luciferase-based reporter (BLI). For fixed tissues, ex vivo samples, or studies involving protein, peptide, or small molecule tagging, fluorescence imaging (FLI) is more suitable. When using FLI, consider fluorophores with minimal spectral overlap and, for in vivo work, those in the near-infrared (NIR) range to minimize signal attenuation.

In general, long wavelength red light (especially > 650 nm) will penetrate tissues better than short wavelength blue/green light (400 – 500 nm), especially at depth and in tissues with a high level of hemoglobin. However, there are several additional factors to consider, including:

- short wavelength blue/green light is usually brighter (higher quantum yield) than long wavelength red light;

- both luciferases and fluorescent proteins can possess broad wavelength distributions (up to several hundred nm, from blue to red). Thus, although a predominantly red light source will work most efficiently at depths, in some instances a brighter predominantly blue light source will penetrate better at shallow (e.g., subcutaneous) tissue depths.

This choice depends principally on the biological process and disease model being imaged. Bioluminescence is significantly more sensitive than fluorescence, especially at depth in an animal. However, most luciferase-based reporters need to be genetically encoded and expressed inside a cell, making labelling slower and more laborious than fluorescent imaging with chemical fluorochromes (fluorescent proteins require similar effort to luciferases). In addition, fluorescent reporters, which are available in a wider array of wavelengths, are better for tracking multiple targets simultaneously, as well as for translational models (e.g., image guided surgery). For more info on optical imaging probes and reporter expression, please read: https://spectralinvivo.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Reporter-Expression.pdf

There are several luciferases, of both terrestrial and marine origin, that have been used for preclinical imaging of disease in small animals. Factors such as availability, cost, substrate distribution (PK/PD) in vivo, wavelength, brightness, toxicity (substrate), immunogenicity, oxygen tension dependency, energy dependence (e.g., ATP), and size, are all important considerations.

Firefly luciferase: By far the most widely used luciferase is North American firefly luciferase (FFluc), whose mammalian optimized DNA, found in plasmids, viral vectors, engineered cell lines and transgenic animals, is relatively easy to obtain and whose luciferin substrate is inexpensive, with very good in vivo biodistribution. Moreover, at 37°C, this luciferase has a peak wavelength of 612 nm, with a significant proportion of this light emitted beyond 650 nm. Brighter variants of FFluc, such as AkaLuc, have been engineered, which, in combination with its novel substrate, Akalumine, has a peak bioluminescent wavelength of 650 nm. However, this substrate is more expensive.

Red and green click beetle luciferase: Both red and green click beetle luciferase are strong contenders with firefly luciferase, working equally well in vivo using firefly luciferin as a substrate. At shallow depths, the two click beetle luciferases can be used in combination and discriminated due to their different wavelengths (green – 537 nm, red – 613 nm), but this ability disappears at depth. Both click beetle luciferases are more stable than firefly luciferase at low pH.

NanoLuc luciferase: This very small, very bright luciferase is a great complementary reporter to firefly luciferase (for dual imaging methodologies, such as a NanoLuc labelled CAR T-cell targeting a FFluc labelled tumor) and superior BRET (e.g., NanoLuc fused to a long Stokes shift fluorescent protein) capabilities. Although its peak wavelength of 460 nm is far from ideal for imaging at depth, its superior brightness (100x – 1000x brighter that firefly luciferase) makes it a viable in vivo reporter, particularly at shallow depths. Moreover, because this luciferase is energy independent (not requiring ATP), it can be used to tag targeting antibodies and can be expressed on the surface of cells, unlike firefly luciferase which requires ATP. The in vivo substrate for NanoLuc, fluorofurimazine, although significantly more expensive than firefly luciferase, also has good in vivo biodistribution.

Renilla luciferase: Conventional renilla luciferase (peak bioluminescence at 480 nm) is not as bright as NanoLuc and its substrate, coelenterazine, is somewhat toxic and has poor biodistribution. Derivatives of renilla, such as Super Rluc8 (peak bioluminescence at 540 nm), have been developed that are considerably brighter, but more difficult to acquire.

Gaussia luciferase: Like NanoLuc this is a small, bright luciferase with a peak bioluminescent wavelength of 460 nm. However, the substrate for this luciferase is coelenterazine, which makes it less ideal for in vivo imaging, as discussed above.

Bacterial luciferase: The bacterial lux operon (luxCDABE) from Photorhabdus luminescens has been engineered into a vast array of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. This luciferase operon functions to give bioluminescence (peak wavelength of 480 nm) without the need for exogenous substrate. Versions of this operon have been generated that work in eukaryotic/mammalian cells, but this reporter construct hasn’t been extensively studied or adopted for animal imaging studies.

Optical imaging performance can be influenced by the animal’s pigmentation, fur, and skin thickness, which affect light scattering and absorption. Hairless, albino, or white-furred animals (such as BALB/c or nude mice) are often preferred for optimal signal sensitivity and transmission. If these strains are not feasible, hair can be removed by shaving and/or using a depilatory cream, and red-shifted/NIR reporters (for fluorescence imaging) can help compensate for signal loss in pigmented animals.

Beyond optical properties, it is also essential to choose an animal model that is biologically relevant to your research question. This means selecting a strain, genetic background, or disease model that accurately reflects the physiology or pathology you aim to study; whether that’s immune competence, tumor growth behavior, or organ-specific responses. Consulting existing literature and previous imaging studies in similar models can help guide this choice.

Not always. Hair and pigmentation absorb and scatter light, especially for fluorescence. Nude or albino mice improve signal detection, but black-coated mice (e.g., C57BL/6) can still be used successfully with optimized settings, particularly in BLI. For details on the impacts of animal fur and removal when imaging continue reading: https://spectralinvivo.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/rodent_depilation_v3.pdf

Pigmentation and tissue depth attenuate excitation and emission light, reducing sensitivity. Near-infrared (NIR) fluorophores penetrate deeper and are less affected by pigmentation.

Yes, but signals may appear attenuated due to melanin absorption.

Yes, anesthesia is required to immobilize the animals during quantitative optical imaging acquisition. Isoflurane is most commonly used because it is quick, safe, and compatible with repeated imaging. Sevoflurane, or several injectable methods can also be used but it is best to check with your Vet before proceeding.

In addition to potentially removing hair from the area of interest, it is advisable when performing fluorescent imaging to use a diet that doesn’t contain plant material to prevent non-specific fluorescence from chlorophyll, which can interfere with a wide range of imaging probes (especially those in the 700 – 800 nm range). For additional suggestions, continue reading: https://spectralinvivo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/10Tips_Tricks_5_5_2020.pdf

Recommended controls include:

- Non-transfected or unlabeled cells or animals (background control)

- Vehicle-only injection controls

- Reference animals with known levels of reporter expression

- Spectral Instruments Imaging Calibration Device (SIICD) as a positive control to confirm the system is functioning properly before imaging

These controls help with normalization, interpretation of results, and reassurance that unexpected signals are biologically related rather than due to instrument variability.

Yes. Many researchers collect fluorescence first, followed by bioluminescence imaging. Aura software makes it easy to organize and analyze both data types in a single project. You can use Aura’s Composite Image Manager feature to merge both images into one.

Yes. Both BLI and FLI are noninvasive and allow repeated imaging of the same animal over weeks or months, reducing variability and animal use.

Yes, GFP can be imaged in vivo, but there are important considerations. GFP emits in the green spectrum, which overlaps with tissue autofluorescence and is strongly absorbed by hemoglobin, reducing sensitivity in deep tissues. For superficial imaging (such as subcutaneous), GFP may give good signal, but for deeper or whole-body imaging, near-infrared (NIR) fluorophores are generally recommended for better signal-to-background ratio and tissue penetration.

For more details on how tissue absorption and probe selection affect in vivo imaging, see our tech note: https://spectralinvivo.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Science-of-Optical-Imaging.pdf

Quantum dots are highly effective fluorophores widely used in various applications. However, a significant drawback in preclinical imaging is that their absorption peaks often fall in the violet or ultraviolet range of the electromagnetic spectrum, where tissue penetration depths are shallow.

Delivery methods for fluorescent probes or bioluminescent substrates (luciferins) can include intraperitoneal, subcutaneous, intraorbital, or intravenous injection. The timing depends on the specific agent used:

Substrate (luciferin) delivery: Some protocols recommend imaging a few minutes after injection of the substrate (e.g., 5 – 10 min after subcutaneous injection or 1 – 2 min after IV injection) to capture a peak signal. However, it is good practice to run a substrate/luciferin kinetic study when first developing an animal model to more accurately identify when a peak signal occurs after substrate administration. For example, when using FFluc engineered cells in an animal model, it is recommended that 150 mg/kg of firefly luciferin is administered subcutaneously, and the animals are imaged sequentially every 1 – 2 minutes for a period of 20 minutes. If a signal is particularly weak, 300 mg/kg luciferin can be administered subcutaneously. This same protocol can be used for other substrates (e.g., fluorofurimazine for NanoLuc, or coelenterazine for renilla or gaussia luciferase). However, the route of administration may vary due to the formulation of the substrate.

Establishing the kinetic curve for your specific model is essential, it ensures imaging is performed at the true signal peak for your enzyme/substrate system and accounts for biological factors such as tissue perfusion, substrate delivery efficiency, and reporter expression. This process is now straightforward using the Kinetics Mode in Aura software, which automatically acquires and plots signal changes over time, making it easy to visualize and determine the optimal imaging window.

Luciferin can be administered subcutaneously. This same protocol can be used for other substrates (e.g., fluorofurimazine for NanoLuc, or coelenterazine for renilla or gaussia luciferase). However, the route of administration may vary due to the formulation of the substrate.

Fluorescent probe delivery: There is a vast array of fluorescent probes readily available. These come in a multitude of different wavelengths and chemical formulations. Those that have high quantum yield with excitation and emission wavelengths between 650 nm and 850 nm are most desirable for in vivo imaging. In most instances, these chemical fluorochromes are injected IV and remain in the animal’s tissues for 24 – 72 hrs. If targeted (e.g., attached to an antibody) or activated (e.g., containing a proteolytic cleavage site), imaging is usually possible 6 – 48 hrs after administration.

Establishing the kinetic curve for your specific model is essential, it ensures imaging is performed at the true signal peak for your enzyme/substrate system and accounts for biological factors such as tissue perfusion, substrate delivery efficiency, and reporter expression. This process is now straightforward using the Kinetics Mode in Aura software, which automatically acquires and plots signal changes over time, making it easy to visualize and determine the optimal imaging window.

For more details on our kinetics feature, check out this poster: https://spectralinvivo.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/kinetics_poster_emim_2024_print.pdf and webinar: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0TbgVHyF8lg

Optical imaging is fast, cost-efficient, and highly sensitive, making it ideal for high-throughput screening and real-time data acquisition. Unlike modalities such as PET or SPECT, which rely on radioactive tracers, optical imaging uses non-ionizing light and bioluminescent or fluorescent reporters, offering a safer and more convenient workflow for longitudinal studies.

While PET and SPECT provide high sensitivity and excellent depth penetration for quantitative functional imaging, they require radiochemistry facilities and have higher operational costs. CT and MRI, on the other hand, offer detailed anatomical information with superior spatial resolution and 3D reconstruction capabilities, but they are slower, more expensive, and less suited for dynamic molecular imaging.

Optical imaging complements these techniques by providing rapid functional and molecular readouts that can guide or validate findings from other imaging modalities. As a result, multimodal imaging; combining optical imaging with CT, MRI, PET, or SPECT, has become increasingly common, offering researchers a more comprehensive understanding of both molecular and anatomical changes within the same animal.

For a more thorough comparison of preclinical imaging modalities, continue reading this tech note:https://spectralinvivo.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Comparison-of-Preclinical-Imaging-Modalities.pdf

In vitro imaging provides high control and sensitivity but lacks the complexity of living systems. In vivo imaging captures whole-animal physiology but must account for tissue absorption, scattering, and biodistribution.

Start by verifying your reporter system works in vitro, then move to small pilot in vivo studies. This ensures proper substrate activity, fluorophore stability, and imaging sensitivity. Read this tech note more on this topic: https://spectralinvivo.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/why_move_from_in_vitro_to_in_vivo2.pdf

Potential causes of low signal intensity when imaging cells or animals (transgenic) genetically engineered with a luciferase may include:

- inefficient or ineffective reporter delivery (transfection, viral transformation);

- weak promoter or response element;

- DNA methylation (especially with viral promoters);

- insufficient dose of the substrate;

- incorrect delivery of the substrate (missed tail vein injection with IV delivery or injecting into a fat pad with IP delivery);

- Inadequate PK/PD delivery of the substrate (reduced ability to cross BBB or physical structure/tissue matrices in the animal).

High background fluorescence can be due to a multitude of reasons including:

- autofluorescence from the animal (e.g., diet containing plant material);

- phosphorescent materials (e.g., plastics or dye markers) in the imaging chamber;

- dirty equipment.

Variability can arise from uneven administration of the imaging agent. For the most consistent results, standardize handling protocols and ensure the substrate is distributed evenly. For bioluminescent studies, use Aura software’s Kinetics feature to identify and capture images during the reporter enzyme’s peak plateau time.

D-luciferin is standard for firefly luciferase, while coelenterazine is used for Renilla luciferase. Substrates are typically administered intraperitoneally (ip.), subcutaneously (subQ), or intravenously (iv). Read this tech note for more details on optimizing substrate dosing: https://spectralinvivo.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Optimizing_Substrate_Dosing_for_Reliable.pdf

Perform a kinetics experiment! Aura’s Kinetics Feature automates peak/plateau detection, helping you identify the best time to image for consistent results. For more details, watch this webinar on the Kinetics feature in Aura: youtube.com/watch?v=0TbgVHyF8lg&feature=youtu.be

Use near-infrared probes and place animals on an alfalfa-free diet at least 5 days prior to imaging. For additional suggestions, continue reading: https://spectralinvivo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/10Tips_Tricks_5_5_2020.pdf

Keep substrate dose, route, and timing consistent across sessions. Use Aura’s Kinetics feature during pilot experiments to determine the signal’s plateau phase, then fix this imaging window for all time points. Maintaining consistent anesthesia protocols and imaging temperature also reduces physiological variability.

What researchers are saying...

We were so pleased with the instrument’s performance and SII’s support within the very first year of use that we committed to a replacement of our entire suite of older instruments with SII products.

The LED based illumination meant that there was nearly a 90X more light incident on the surface of the specimen versus traditional white lights used by other manufacturers which translates to earlier detection – sometimes weeks ahead – saving researchers time and money. It also dramatically improved the utilization of the imaging core.

SII has a single-minded focus on building the best optical imaging instruments for bioluminescence and fluorescence. The entire company – management, engineers, sales team and support is aligned around that central focus.

This has meant many good things for us as a customer – where the innovation continues non-stop. We are already seeing many new features in software and hardware that leave us very optimistic about the future.

David M Colcher, PhD

City of Hope

Spectral customer support is excellent. Whenever we reach out to them, they get back to us quickly

We have used our Ami-X intensively for the past four years and have been extremely pleased with the sensitivity and reliability of this instrument, both for NIR fluorescence and bioluminescence capture. Operation is very simple and the system needs almost no maintenance at all. On top of this, technical support is easy to reach and quick to reply with solutions for general use and technical questions. The Aura software is very simple to learn and having unlimited free copies of this program available for all our computers is an enormous advantage for image analysis. In fact, the system is so robust and easy to operate that we use it not only for research but also for teaching in vivo imaging methods in our graduate courses.

Our Ami has been an essential instrument in our lab for a few years now and has always worked reliably, especially during many periods of intensive usage. The Aura software is very user-friendly and intuitive to operate. Communicating with technical support is always a quick and pleasant affair and they have been incredibly forthcoming in replacing some minor lost parts, so that we could continue using our Ami without delay.

We were so pleased with the instrument’s performance and SII’s support within the very first year of use that we committed to a replacement of our entire suite of older instruments with SII products.

The LED based illumination meant that there was nearly a 90X more light incident on the surface of the specimen versus traditional white lights used by other manufacturers which translates to earlier detection – sometimes weeks ahead – saving researchers time and money. It also dramatically improved the utilization of the imaging core.

SII has a single-minded focus on building the best optical imaging instruments for bioluminescence and fluorescence. The entire company – management, engineers, sales team and support is aligned around that central focus.

This has meant many good things for us as a customer – where the innovation continues non-stop. We are already seeing many new features in software and hardware that leave us very optimistic about the future.

The Ami HT system is pretty user friendly. The system was clearly designed to image mice in an efficient and safe way

"We really like the SII Lago imaging instrument because it has several improvements as compared to our previous IVIS® instrument. The second adapter with 10 nosepieces allows us to image up to 10 mice at once, which saves us a lot of time when imaging mice. Additionally, the software is very user-friendly and easy to run. Nice features that we appreciate are the white light inside the instrument that is very helpful for positioning the mice. Also, the button that automatically opens the door of the instrument is helpful. Finally, we noticed that the instrument reaches the temperature in a very short time allowing us to begin imaging pretty much right away and this again saves us a lot of time"

“The support from Spectral Instruments has been excellent. The only issue that we have had with our two LagoX machines was self-inflicted. Aggressive firewall and anti-virus software that we installed on the computer resulted in a camera initialization issue. Spectral Instruments responded immediately and was on site within 48 hours. They worked with us to identify and correct the issue. It is refreshing to work with a company that is personally engaged and takes pride in the quality and support of their product.”

I have been extremely pleased with SII. Bo Nelson and the team has been outstanding with helping me with filter selections and filter exchanges based upon fluorophore requirements, ensuring the instrument is operating to specifications, with new software updates and any problems, albeit rare, we are having with our Ami. The system is super robust and easy to train users. Another huge benefit is the software is free, allowing me to refer to our users to SII website and thereby allowing them to analyze the data on their own PCs saving time and money.

We are very happy with the Lago and LagoX systems. Great customer service too.

[I am] impressed with its robustness and its abilities to detect a wide range of labels and sensitivity of detection.

Due to the frustrating customer support experiences related to our Perkin Elmer's IVIS® instrument, we decided to give the Lago X a shot. As a core laboratory, we offer it to multiple research groups. Our users transition from IVIS® to Lago was seamless. They are pleased by the faster cooling of the Lago camera, the higher animal capacity of the imaging chamber, user friendliness of the [free] Aura software (additional IVIS® desktop analysis software copies must be paid for)

We have a great relationship with Bo, Andrew and the SI team. Getting hardware or software support from them is just so easy!

Having the ability to easily image up to 10 animals at a time has been such a time saving bonus! I can get my data collected twice as fast which allows me more time for data analysis and coffee! The Lago is very intuitive and so easy to use. I have been using the system for over a year now and have not yet ran across any type of malfunction issue, my previous equipment would require constant troubleshooting.

In our laboratory, we have found the AMI imaging system to provide reproducible BLI imaging data in the context of orthotopic pancreatic and ovarian tumors in mice. As these tumor types are located deeply within the mouse, it was essential to have a system that had high sensitivity. One aspect of the AMI that we find to be highly important is the reproducibility of the images including that the signal detected from each mouse is independent of the relative order of the mouse within the system, i.e. mouse 1 has the same signal regardless of if it is in the 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 position within the mouse holder. Additionally, we have found the NIR fluorescence to be of high sensitivity with the ability to differentiate signals at 680nm, 715nm, 750nm, and 800nm. Perhaps, the most important aspect of our experience with Spectral Instruments Imaging has been that they are very receptive to aiding the users and provide exceptional support even well after our instrument purchase

I have had over 20 years experience utilizing bioluminescence imaging in mouse models of cancer in both industry and academic settings. This technology is essential for the work performed by my lab and with our collaborators. Much of our work is done with orthotopic and metastatic tumor models, but we also use it for luciferase-enabled genetically engineered mouse models. We use bioluminescence imaging to evaluate biologic aspects of tumor progression and metastasis as well as response to experimental therapeutics. For the past 5 years, we have exclusively used the Spectral Instruments AMI HTX system having switched from our IVIS® 100. We have been impressed with the relative performance of the AMI HTX system, from its rapid startup, stability, sensitivity and the ease of using Aura software, which is freely available to my collaborators facilitating our studies. Spectral Instruments has been a pleasure to work with over the years responding rapidly to any questions that emerge. I am highly recommending this system to anyone who uses this technology.

We have never experienced such an excellent customer relationship with any other vendor and are truly appreciative.

Our core runs the Ami users all enjoy the machine. The software update with easy mode has been great for new users to have a guided trial for different tests. As the trainer for the past few months and managing this machine, I have collected a lot of feedback. We are able to produce clear images with greater ease than the IVIS® system. Having a centralized mechanism for x-ray, fluorescence, and bioluminescence has been a great tool for all users. Using the Ami-HTX, we have been able to use a hypoxia-targeting dye to confirm the hypoxia status of two cancer cell lines

I would definitely say I prefer the Ami HT to the Xenogen IVIS®. The software is intuitive, the nose cone setup is more flexible, and the resolution is better, but by far the best feature is how quickly the camera sensor cools down. No more waiting around for ages if you forget to pre-cool the instrument!